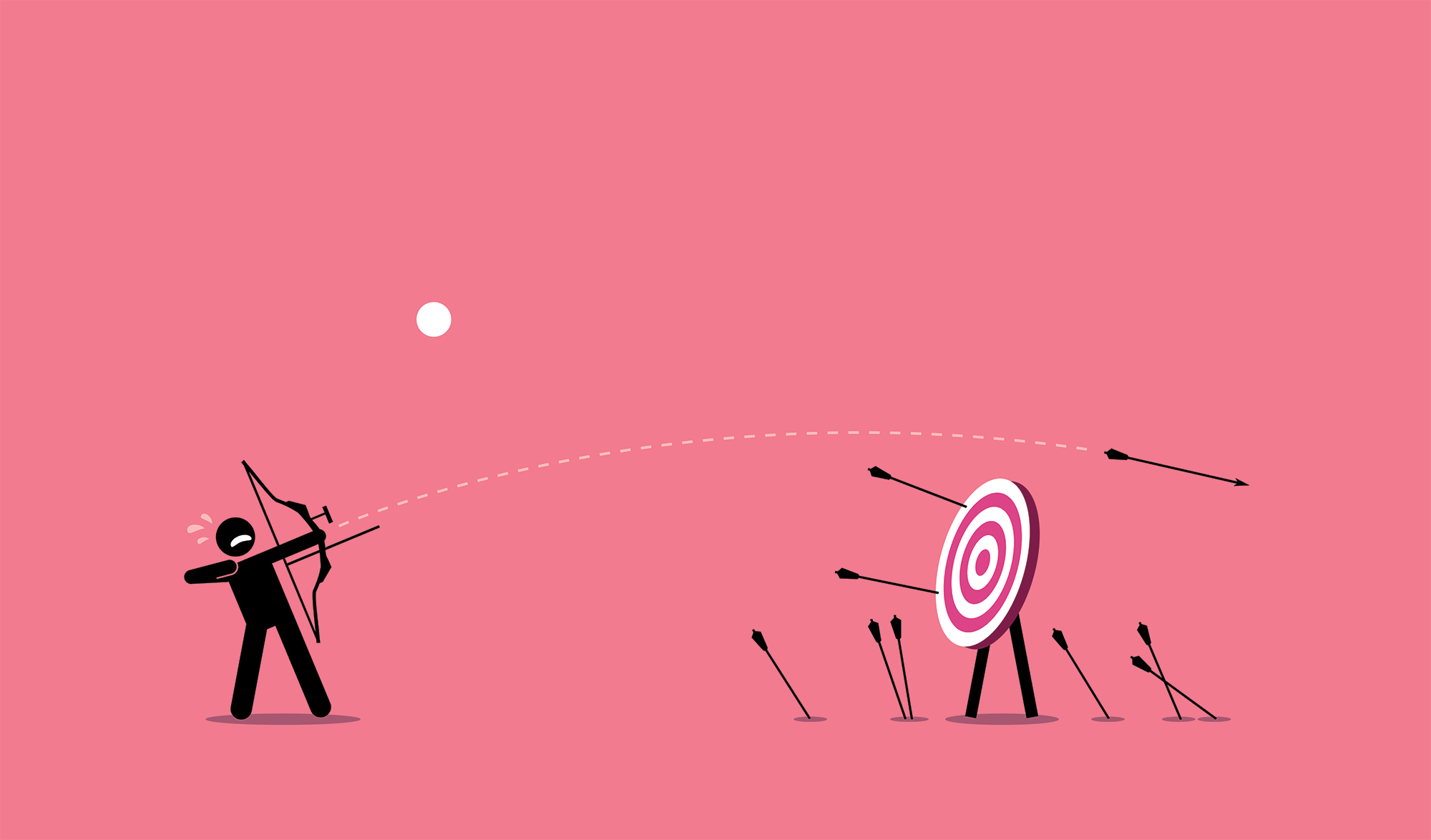

Let’s start with a statistic: According to our syndicated design effectiveness data, more than 50% of package redesigns fail to increase purchase preference compared to their predecessors. The brands that undertake these redesigns are not small or undisciplined, either; these redesigns very likely used standard end-of-process validation tools and met action standards. Nevertheless, when sampling redesigns that likely made it through these established processes, the failure rate is incredibly high.

This intrigued us, so we ran our own consumer evaluations of these redesigns. We tracked the sales data of more than 50 redesigns launched to market, cross-referencing their sales performance with our own consumer data—and the results showed the correlation we anticipated. Nearly every redesign that improved purchase preference also increased sales. Conversely, the designs that performed worse on this metric declined in sales. In other words, purchase preference (as measured by Designalytics) has a near-perfect correlation with sales outcomes.*

.png?width=2500&name=measurement_comparison%20(1).png)

It’s clear that beyond the obvious issues with a coin-flip failure rate, there’s something else at play. The consumer-packaged-goods (CPG) industry is laboring under the mistaken impression that design does not drive business outcomes because—until now—they have seen no clear connection between the validation scores a redesign receives and the sales of that product once the redesign launches. Because brands and marketing mix analysts couldn’t see the impact, they assumed there wasn’t any to speak of.

The truth is: Design doesn’t have an impact problem. It has a measurement problem.

Or, rather, it did have one. Designalytics’ empirically-validated syndicated design performance measurement tools can be used to test pre-market designs with higher than 90% predictive reliability of whether the redesign will outperform its predecessor in sales. Our unmatched data quality, massive sample sizes, new-to-industry metrics, advanced exercise design, and much more have completely changed quantitative package design testing.

This does beg the question, though: Why do so many redesigns that leverage traditional research tools fail?

There can be many reasons. Here are a few:

Testing too late in the process

Historically, many large brands have chosen not to conduct robust research that would help guide creative strategy at the beginning of the design process (an unfortunate consequence, perhaps, of the mistaken belief that design is not impactful). Instead, they’ve focused on intensive research, such as shelf tests intended to replicate store environments, at the end of the process to validate their chosen design route—much too late to provide vital direction to the creative team.

The result of this approach is less informed creative strategies, an increase in subjective decision-making, and limited opportunities for creative exploration and refinement that could've created higher-performing designs. Importantly, though, this trend seems to be shifting: Brands have begun to notice the value of doing research earlier in the process.

Parity-or-better action standards

In general, the accepted measure of success for a traditional validation design test is “parity or better.” Now, if you asked a random collection of brand managers (or people in general) what “parity” means, most would probably say “equal” or “as good as.” For good reason, too: that’s basically the dictionary definition. In traditional validation testing, however, parity is a statistical term with a divergent meaning: that the sample size is too small to have confidence that the new design is better, worse, or exactly the same. In other words, parity amounts to a very expensive, anticlimactic shrug.

To make matters worse, parity is the outcome for a vast majority of design tests because lower sample sizes (i.e., 100-150) are often used. Given the confluence of these factors—the coin-flip success rate and the frequency of parity results—the bar for design performance metrics has been lowered to accommodate the high incidence of parity results. As a consequence, brands are given the “green light” more often… but at a potentially significant cost.

Considering the high failure rate of tested designs and a low correlation to in-market outcomes, brands rarely question this entrenched idea, because they think it means design doesn’t have a significant impact.

It definitely does have an impact, though, and our data consistently bears that out. In fact, our design research arrives at a parity result for less than a fifth of our redesign tests—which means we deliver a decisive and predictive outcome around 80% of the time. That kind of clarity leads to a higher degree of confidence; Brands can see clearly which design works better and why, without a post-hoc dive into the numbers to justify their decision.

Focusing on the wrong measures

When companies conduct package design research, they often don’t know which design performance factors are most important. Lacking solid, validated data on what matters most in a package design’s performance—in other words, the metrics most likely to impact sales for the product—they focus on the wrong things.

Take design appeal, for example. Intuition would dictate that a package design consumers actually like would excel, right?

Not so fast. Turns out, likeability is even less predictive of sales gains than a coin toss. According to our meta-analysis of hundreds of redesigns across scores of categories, improvement on likeability scores correlated with highly-predictive purchase preference results only 46% of the time.

This isn’t to suggest that masterful creative talent isn’t essential; it just means that packaging can’t only be visually appealing—it needs to be strategic too. Most importantly, the design needs to communicate well. We’ve found that effectively communicating important product attributes on your package contributes heavily to sales performance, with a nearly 90% correlation to directional in-market outcomes.

Failure to evaluate current design’s performance

There’s a reason the old adage isn’t “If it ain’t broke, let’s invest immensely in an uncertain alternative.” The truth is that some package designs are performing well already. If they do require a redesign, the data often indicates a targeted change or two can pay big dividends, while a more aggressive redesign might actually hinder sales.

Assessing your package design on a regular basis arms your organization with the insights to know when a redesign is warranted and, if so, what changes will likely drive growth. Otherwise, decisions can be based on fear, conjecture, or just opinion.

“Brands make a lot of assumptions—thinking we need to redesign because the competition did, or to keep things fresh, or for this or that reason,” said Jen Giannotti-Genes, global brand design director at Colgate-Palmolive. “But we need to have very up-to-date learning about what's working and what’s not before we just go and change everything. Conducting pre-design research on the current package is incredibly helpful at that stage.”

Here’s an example of how it can go wrong. A leading snack brand redesigned the packages of four of its signature products. The process took two years, included multiple agencies, and had broad stakeholder involvement. Like many large CPG brands, the brand almost certainly used traditional validation testing… at the end of the process, after virtually all of the work had been done and subjectively assessed. The new design was given the “green light” and launched to market.

Immediately after it hit shelves, we used our first-of-its-kind system to measure the performance of each redesign against its predecessor with consumers. (We create Redesign Response Reports like these for any redesign in a category as part of our syndicated research subscription). The results were stark: To varying degrees, each of the tested new alternative designs performed worse than the original.

After six months, we assessed the sales data for each: The numbers were down across the board, which resulted in a -$33.4 million annualized impact on the brand’s bottom line.

Having access to more predictive data at the end of the process would have likely prevented this false positive, saving millions. And if the brand assessed the designs at the beginning of the process (which, as noted above, Designalytics always recommends to our clients), it would have put the design on the right track, sparing the brand sunk design and research costs, avoiding possible damage to brand equity, and potentially netting millions in growth.

Each redesign has its own story of success or failure. With Designalytics, you now have the opportunity to see potential failures before they arise, leverage objective insights to maximize successes, and actually see the impact your design can have in the growth of your brand.

Clarity. It’s a lot better than a coin flip.

*This correlation is binary. Designalytics reliably predicts whether sales will increase or decrease, but not by how much.