When clients approach us with a need for package design research, they will sometimes request we specifically target consumers who purchase their brand in addition to the larger pool of category buyers. The idea is to get an adequate sample of both audiences and ensure that, in attempting to appeal to a broader audience, the brand isn’t alienating its loyal customers.

We understand this inclination. After all, It’s natural to want to arm yourself with more targeted data when making decisions, and many clients want to ensure they are considering their most important constituency—their current buyers—when they redesign.

While we can and have accommodated these requests, we usually suggest that there might be a better use of funds (like developing and screening more designs, for example). Why? Because we have gathered data on many package designs and redesigns across dozens of product categories, and we’ve seen very few compelling cases of targeting (beyond category buyers) that made an appreciable difference in the consumer results.

In our experience, the only things hyper-targeting adds to a research project is 1) cost, and 2) time. In other words: Your brand’s investment may increase with this approach, but your return on that investment likely won’t.

Why hyper-targeting isn’t helpful in the long run

- Focus too much on the trees, and you may miss the (profitable) forest

It’s important to remember that your target market may be larger than you think… or it may change.

Consider ThinkThin, a protein-bar brand started in 1999. At its launch, the package was designed to appeal to a specific segment: health- and diet-conscious women. Over time, the brand discovered that 40% of their consumers were actually male and were driven, in part, by the amount of protein in the bar.

The hyper-targeted package design and their current branding were holding them back. “We couldn’t ignore the guys in the room any longer,” said Melissa Astete, Senior Brand Manager at the company, at the time. “Dropping the ‘Thin’ from our brand name and emphasizing the protein call-out has definitely expanded our user base.” The package design was also a big success and garnered a Designalytics Design Effectiveness Award in 2020.

- It extends research timelines

At Designalytics, we pride ourselves on a data-driven approach and we don’t cut corners. For example, our on-demand package design research includes samples that are four times the industry average. Plus, we're the only design research firm to ensure “first-view” data quality, which means each online activity utilizes a new set of consumers. This ensures the data is “fresh” and not distorted by repeated exposure to the same brands.

Such a statistically rigorous methodology has been proven to yield consistently more reliable and decisive results, but it also requires more consumers. This can mean extending research timelines and, relatedly...

- It increases the cost of research

The extra time and effort to find most-likely-to-buy consumers increases the cost of the research considerably. That wouldn’t necessarily be a bad thing… if it improved the quality of the findings. We simply haven’t found that to be the case.

So… what does the data say?

Our syndicated redesign database is a treasure trove of data that is ideal for an objective view on this topic. The raw data we collect from consumers includes a “brand purchased most often” (BPMO) question from which proxy subgroups of current brand buyers can be constructed. So we decided to dig into this data and ask: Are brand buyers' responses significantly different from those of category buyers in the context of design research?

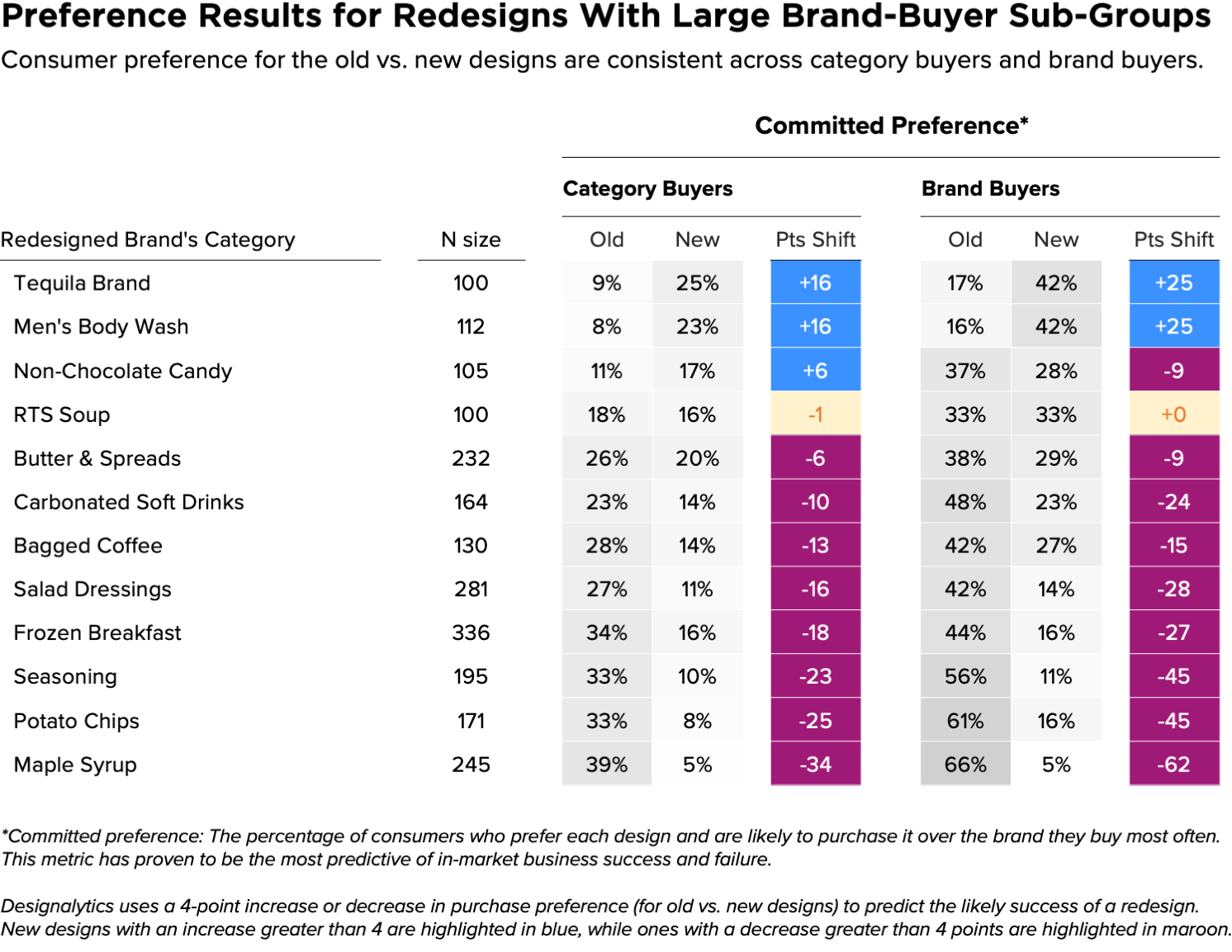

For this exercise, we randomly chose studies for more than 30 different redesigns. First, we’ll focus on the 12 which had a very high number of respondents (100 or more), since the validity of their results will be highest. Those dozen redesigns were spread across a range of categories (from body wash to bagged coffee), and for each one we compared redesign performance for the BPMO subsets to the overall performance among general category buyers.

As a basis of comparison, we used our most predictive measure: committed purchase preference, which refers to a consumer’s willingness to purchase the brand in question over the one they currently purchase most often. Our research indicates that this metric correlates with positive and negative business outcomes 95% of the time.

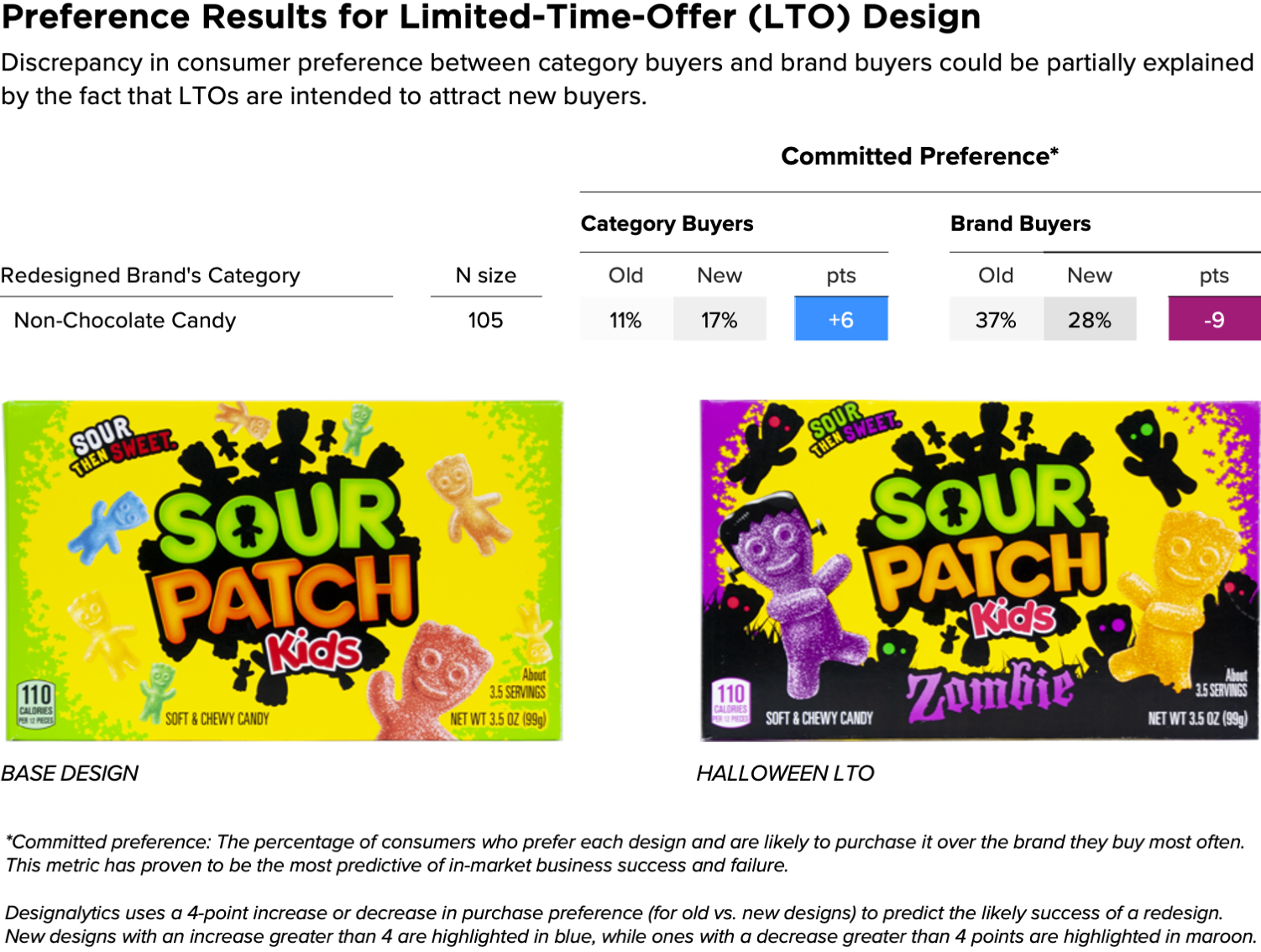

The results were as expected, but were even more emphatic than we anticipated. In 11 of the 12 cases with high BPMO sample sizes, the subgroup consumer response was consistent with that of the overall category buyer group; Designalytics’ recommendations would have been the same for the two groups. The only exception was a limited-time-only (LTO) Halloween candy package, which requires an important caveat: LTO designs are typically intended to invite new buyers into a brand. As long as the current design was still available, this novelty design may have successfully attracted some non-brand buyers without any current buyer alienation.

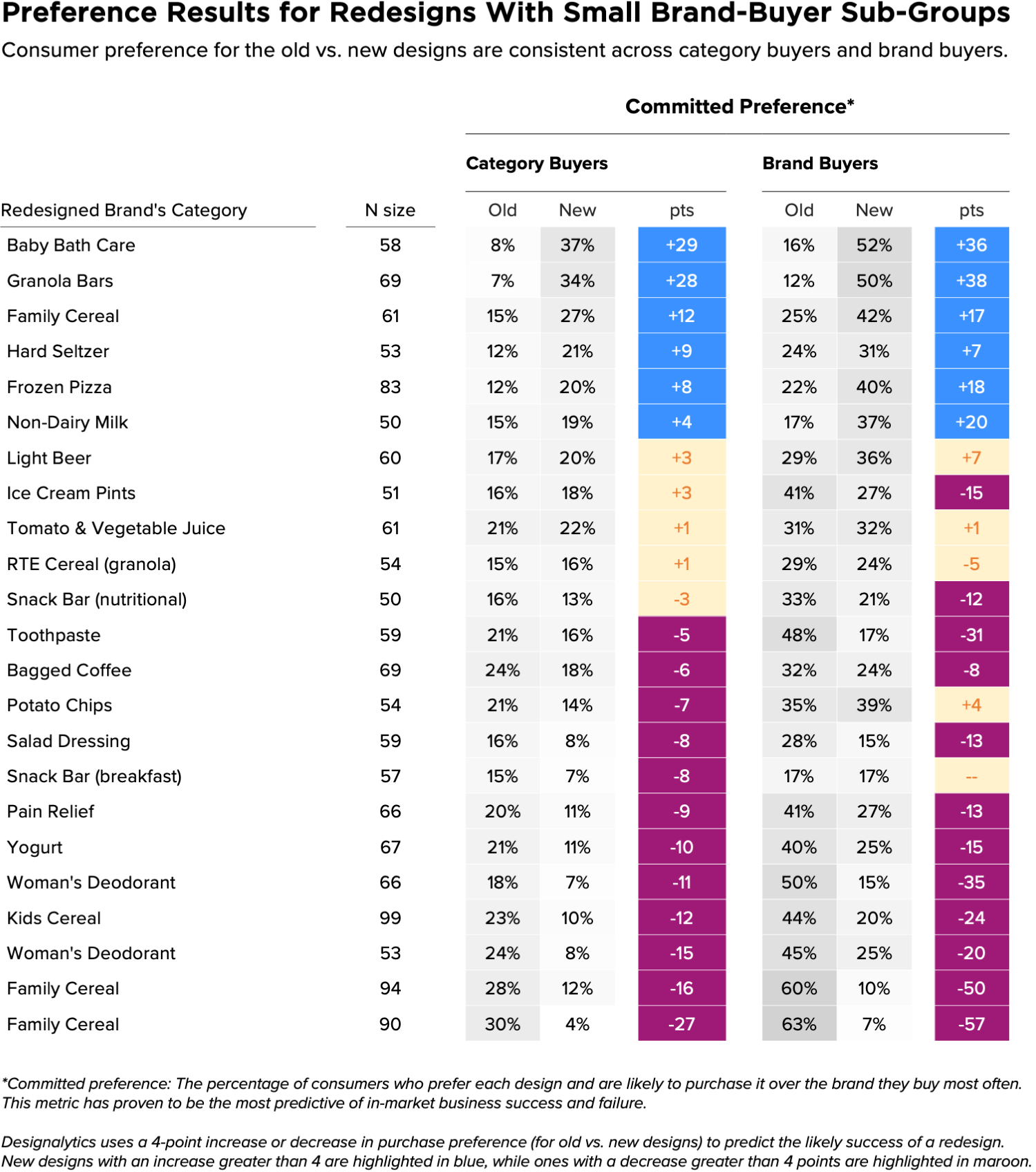

We also received results from subgroups with fewer than 100 consumers. While we never recommend drawing conclusions from smaller samples, it's worth mentioning that even in these small-sample subgroups, consumer responses remained consistent between the category buyer aggregate and BPMO subgroup. In fact, only the previously-cited Sour Patch LTO presented a reversal of performance. The other 97% of cases affirm the conclusion that targeting to the BPMO level does not make a marked difference in results.

Hyper-targeting is unnecessary with our system

At Designalytics, we’ve developed a methodology that is much more fine-tuned than traditional research tools. That means we’re able to deliver decisive, non-parity results the majority of the time, and it removes the need to drill down further with a subset of brand buyers.

We serve our clients by not only providing the robust, empirically-validated design research for which we’re known, but by acting as a trusted voice on the most streamlined and cost-effective methods of conducting that research. And while deeper targeting is helpful in other marketing endeavors, we’ve found it doesn’t offer a sufficient return on investment for package design.